TikTok as poll battlefield: Lies spreading unchecked

(First of two parts)

MANILA, Philippines — When 24-year-old architecture student Jam created a TikTok account in 2020, she used it mainly to view general designs or videos of mothers making creative lunch boxes for their kids.

The content she sought was harmless, but the app became addictive and she found herself stuck on it for hours.

When the election season rolled in, political content started seeping into her app feeds. It was a hodgepodge of many things, but it was mostly about Vice President Leni Robredo and former Sen. Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the two main rivals in the 2022 presidential elections.

Jam said many of the videos tended to disparage the Vice President.

One that went viral quoted Robredo promising that she would lead a government “na hindi lang corrupt …” (that is not only corrupt). Her opponents pounced upon this incomplete remark which drew comments like “yare, di lang daw corrupt, ano pa kaya?” (we’re doomed, not only corrupt, what else?).

In fact, Robredo said that she and her running mate, Sen. Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan, promised a clean and transparent government, even if it had only a little money to work with.

“There are a lot of videos like that that create lies out of nowhere,” Jam said. “They try to make her appear dumb.”

Propaganda battleground

It’s illustrative of how TikTok has been transformed from a platform for anything from recipes for pies to dance moves, into a crucial battleground for political propaganda.

These days, three-minute TikTok videos, savvily edited and layered with catchy tunes, could make or break a candidate’s narrative and branding — or even invent new “truths.”

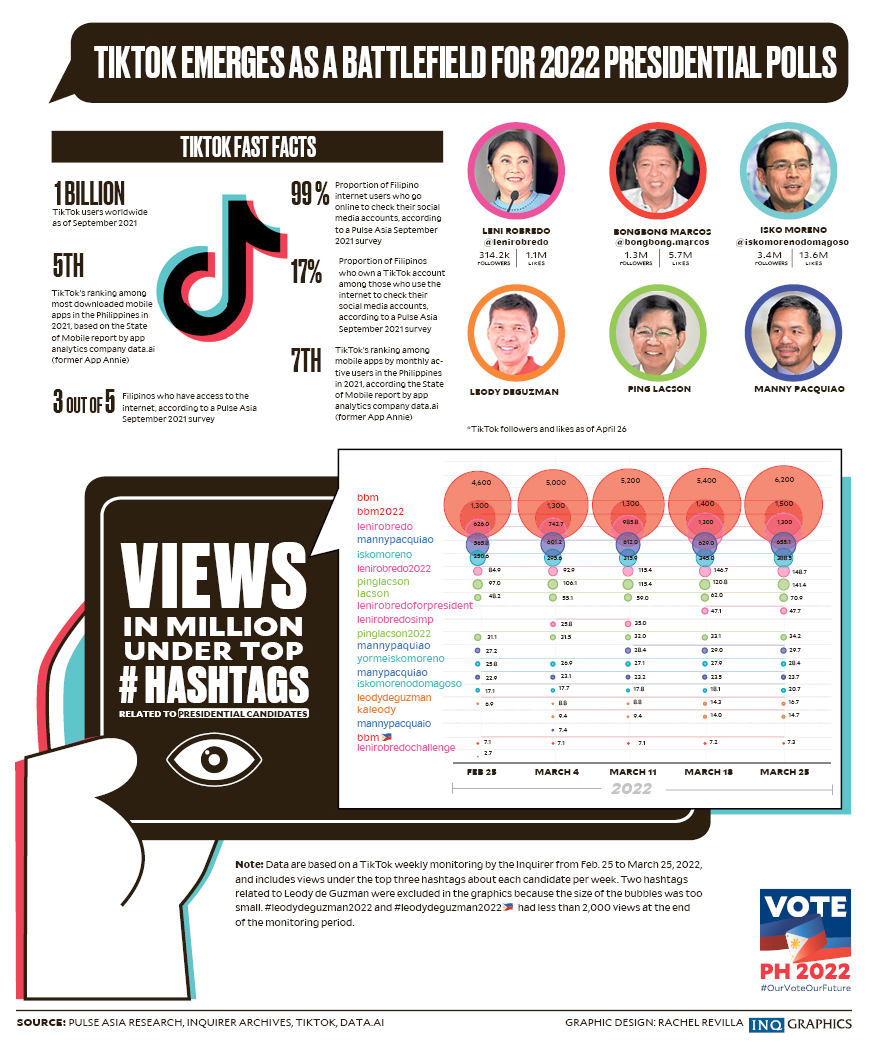

A monthlong analysis by the Inquirer of the top hashtags and most watched videos on TikTok for the six most prominent presidential candidates — Robredo, Marcos, Francisco “Isko Moreno” Domagoso, Manny Pacquiao, Panfilo Lacson and Leody de Guzman — bears this out.

The presidential aspirants and their supporters have been using TikTok heavily to package their platforms, personalities and idiosyncrasies into bite-sized, shareable videos, while also putting down their rivals.

Emotional effect

The most-watched TikTok videos of Marcos are those that dramatize his relationship with his late father, the ousted dictator. One video that raked in 14 million views as of April 26 showed the former senator touching a bust of his father held up by a supporter in the crowd during one of his motorcades.

Such TikToks, which make no explicit claims, aim to “dramatize or heighten emotional effect among the viewers,” according to Celine Samson, head of the online verification team of Vera files.

“It can be so compelling that it has the chance of making other disinformation more believable,” she said.

There were videos whitewashing the atrocities committed during the Marcos dictatorship. But most of the top viewed videos about the Marcoses paint them as a likable, relatable family, with good looks and enviable lifestyles.

Joel Ariate, a researcher at the Third World Studies Center of the University of the Philippines, whose work is centered on the life and legacy of the Marcoses, noted that this was straight out of the dictator’s own playbook: to project himself as a “man of the people: someone who is caring, compassionate.” As they promote their candidates, TikTokers also put down their rivals, and it was Robredo who was worst hit by the attacks on the platform.

Historians and fact-checkers fear that TikTok could be a new means to spread disinformation that can evade scrutiny.

“Because such content is in the realm of images and symbolism, they can now create content that is outside the ambit of fact-checking,” Ariate said.

Billions of views

Samson said it was impossible to correct video materials “where there are no claims.”

“It’s not always that disinformation constitutes something that is fact-checkable, though you’re aware that it’s meant to manipulate people,” she said.

Launched by Beijing-based ByteDance in 2016, TikTok is now the sixth most active social media platform in the world with 1 billion active users globally. In the Philippines, it’s the fifth most downloaded mobile app with at least 36 million active users age 18 and above, according to industry estimates.

In the beginning, the app allowed account holders to upload 15-second videos. That was raised to three minutes in 2021 and up to 10 minutes this year, still much shorter than what is allowed on YouTube and Facebook.

Tony La Viña, the lead convener of the Movement Against Disinformation, said this was “exactly why TikTok has become relevant in the context of the 2022 elections, (where) the majority of the 2022 voters are the youth vote. [That] and the nature of short-form videos itself: one (false) video can destroy hours of your work in terms of explaining something.”

From Feb. 25 to March 25, an Inquirer team monitored the top three hashtags for each of the six candidates as well as hashtags pertaining to the general elections, and the most viewed videos under them.

It collated the videos and tabulated the view counts, likes, shares, and comments, as well as related hashtags, to determine the breadth and depth of engagement and reach of the TikToks. It also tried to classify any claims into five categories: false, misleading, accurate, needs more context, or not fact-checkable.

Marcos’ TikToks amassed billions of views, far more than his rivals.

Marcos’ most viewed hashtag—#bbm—surged from 4.6 billion to 6.2 billion in five weeks. The hashtag #bbm2022 recorded 1.5 billion views.

In comparison, Robredo’s most viewed hashtag — #lenirobredo — hit the billion mark only during the fourth week of monitoring. Her other top hashtags collected views ranging from 2 million to 148.7 million.

Hannah Barrantes, a lawyer who studied the platform’s algorithm, believes part of massive engagement is due to the app’s tendency to lock users in an “echo chamber” where a TikTok post is shared multiple times among fellow supporters.

Samson said it was also possible that TikTok videos were “overperforming” because they are being cross-posted on other platforms like Facebook.

“There is amplification, and at the same time, it’s coordinated. You can sometimes see multiple groups and accounts posting at the same time, so you see it’s also networked,” she said.

In Robredo’s case, most of her top engaged videos were about her campaign and massive rallies. Some are about her relationship with her three daughters, Aika, Tricia, and Jillian, while others are videos of speeches of celebrities who support her candidacy.

‘Damaging rhetoric’

There were videos that belittle her or magnify minor mistakes to peddle the narrative that she was “lutang,” or someone who is not in touch with reality.

This, Ariate said, was one downside to social media. While it democratized content, it also “opened the floodgate to damaging rhetoric” that “does not necessarily have to be true,” he said.

“You can splice videos of Leni to create something else,” he said.

“Before, under the dictatorship, satirists used humor to point out absurdity,” said Ariate. “But now what is being done is to take uplifting messages and twist the message, not to show hypocrisy but to show your capacity for distortion … to squeeze out a lie from something that said a truth.”

Compared to the two frontrunners, the other presidential candidates had relatively unremarkable content that mostly featured their platforms, speeches or other elements from their campaigns. The Inquirer did not come across much fake news pertaining to them.

Domagoso’s most viewed hashtag — #iskomoreno — got 388.5 million views.

His most viewed videos included dance challenges and showed him waving the “two joints” hand sign in one of his caravans. Moreno denies that the hand sign, which is associated with marijuana use, is about illegal drugs. It symbolizes Y for “Yorme,” one of his monikers, and O for Ong, referring to his running mate Willie Ong, he said.

Pacquiao’s top hashtag — #mannypacquiao — obtained 655 million views and the most popular of them were related to boxing.

At the end of the monitoring period, views under Lacson’s top hashtag — #pinglacson — grew to 141.4 million while the most viewed hashtag of De Guzman — #leodydeguzman — had 16.7 million views by March 25.

(To be continued)

EDITOR’S NOTE: THIS REPORT WAS PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF INTERNEWS PHILIPPINES

RELATED STORIES

SWS survey: Majority of Filipinos believe ‘fake news’ is serious issue

Marcos Jr. winning PH poll misinformation drive – analysis

Robredo: Disinformation, fake news still biggest challenge to presidential bid

Subscribe to INQUIRER PLUS to get access to The Philippine Daily Inquirer & other 70+ titles, share up to 5 gadgets, listen to the news, download as early as 4am & share articles on social media. Call 896 6000.